-

1968

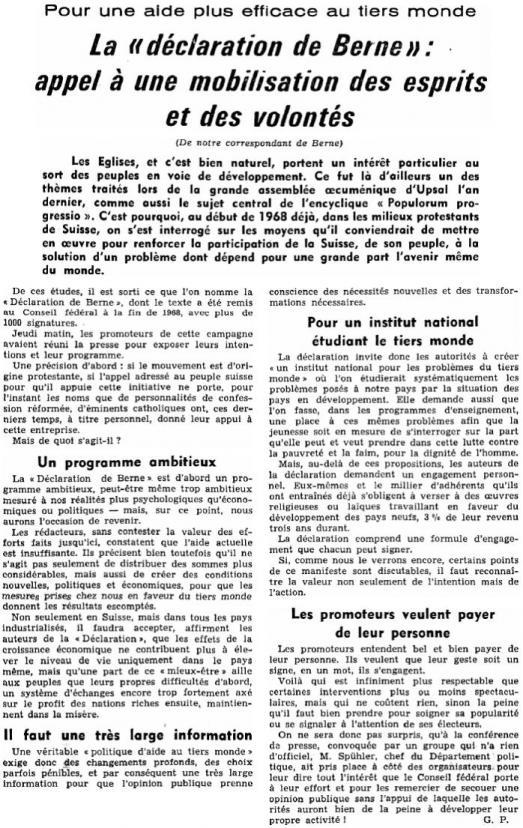

The Berne Declaration, a founding text

1968

A working group comprised of progressive theologians drafts the Berne Declaration. The manifesto calls on the Federal Council to commit to implementing the “requisite political changes” to make relations between Switzerland and poor countries more equitable. The Berne Declaration obtains over 10,000 signatures. The first signatories pledge to donate 3% of their revenue to one or several charities for three years. The movement gives rise to Switzerland’s first independent development NGO.

-

1974

Workshop in Gwatt

1974

In November 1974, the Berne Declaration organises a conference with over 100 participants from its regional groups as well as political and ecclesiastical circles. It inaugurates a practice which has since been repeated within the Berne Declaration and which consists of uniting reflection and action in the fields of:

- Fair trade with the Ujamaa coffee project and support for the action on bananas

- Food policy with the waste of resources in agriculture: “Weniger Futter für das Vieh der Reichen aus Nahrungsmitteln der Armen”

- Education with the problem of racism in school books and children’s books.

-

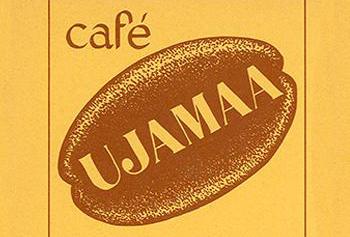

1974

Sustainable coffee from Tanzania

1974

Following an action carried out by students of Berne, in 1975, the Berne Declaration arranges for instant coffee fully produced by a cooperative in Tanzania to be sold in Switzerland. The value-added part of the process remains in Tanzania, meaning that the coffee contributes to the country’s development. In Swahili, the name of the first fair-trade product – Ujamaa – means “the meaning of family in its broadest sense, where everyone works together and shares the fruit of their efforts”. In collaboration with charities, the Berne Declaration sets up the import company OS3 (Organisation Suisse-Tiers-Monde) and contributes to the development of fair trade in Switzerland.

-

1975

Arm wrestling with Nestlé

1975

The Berne Declaration publishes the translation of a book published by the British NGO War on Want, under the title “Nestlé Kills Babies ”. It shines a spotlight on the aggressive manner in which Nestlé is marketing powdered baby milk in countries of the South, to the detriment of breastfeeding. The multinational files a complaint alleging libel with a court in Berne. A year later, the judge upholds the complaint but the Berne Declaration (defended by the then young and little-known lawyer Moritz Leuenberger) is fined a mere CHF 300. The judge recommends that Nestlé change its practices “if it wants to avoid being reproached for immoral and unethical behaviour in the future”. The trial is a victory for the Berne Declaration, which takes advantage of the media attention it attracts to denounce the irresponsible practices of the Vevey-based company.

-

1975

Launch of a campaign against racism and ethnocentrism

1975

The Berne Declaration attacks racism with children’s books, defining criteria for children’s literature that is respectful and publishes an annual brochure on the topic (now called “Fremde Welten”). The Berne Declaration designs educational material and takes the topic to schools, editors and training centres.

-

1976

The jute project

1976

The Berne Declaration launches another visionary project – selling handmade jute bags produced in Bangladesh, with four important messages: work for Bangladesh, the preservation of the environment and of energy, the shift to a simpler way of life and another form of growth. Over 250,000 bags are distributed; these bags also symbolise the war on plastic, which has already been identified as “one of the main sources of waste and pollution of our time”.

-

1977

The banking initiative

1977

The Berne Declaration joins forces with the socialist party to launch an initiative specifically seeking to lift banking secrecy regarding tax matters. In April, the “Chiasso scandal” involving Credit Suisse’s branch in Tessin shows that the success of Switzerland’s financial sector is largely due to the tax evasion practiced by foreign taxpayers. Together with development organisations, the Berne Declaration launches the Action on Switzerland’s financial sector – Third World. Through research and investigation, the Berne Declaration supports the socialist party’s initiative specifically seeking to lift banking secrecy regarding tax matters. The initiative is opposed by 73% of voters in 1984 after being lambasted by slogans from the banking community accusing it of seeking to impregnate the economy with Marxist values. Our organisation continues its fight against tax evasion “Made in Switzerland” and its harmful effect on poor countries.

-

1977

Foundation of the akte – Working Group on Tourism and Development

1977

Tourism is becoming a powerful industry and ever more poor countries depend on its revenues. What’s more, tourism encourages the strongest form of cultural exchange between people from the North and the South. In collaboration with charities and development organisations, the Berne Declaration sets up an organisation. With NGOs from the South, the akte – Working Group on Tourism and Development investigates the effects of tourism on poor countries, raises tourists’ awareness of other cultures and supports local enterprises.

-

1977

Launch of the Berne Declaration’s action on Switzerland as a finance business location and other “spin-offs”

1977

In coalition with other organisations, the Berne Declaration sets up the Action on the Swiss Financial Centre, whose primary mission is to support the banking initiative. The Berne Declaration has repeatedly replicated the practice of setting up organisations tasked with a specific project or topic, opening them up to others and finally leaving them to become independent. The association akte – Working Group on Tourism and Development, which addresses the impact of Swiss tourism on countries of the South, and the OS3 import cooperative (now known as the Claro world shops), are set up at the end of the 1970s and are further examples of spin-offs from the Berne Declaration.

-

1980

“Hunger is a Scandal” campaign

1980

The Berne Declaration draws on specific examples to raise consumers’ awareness regarding the cynical link between agribusiness and hunger in the world. Tinned pineapples sold in Switzerland but produced in disgraceful conditions in the Philippines? By demanding products that are “good fro those who produces them, good for the environment and good for my health”, the Berne Declaration exerts pressure on large retailers. With over 9,000 signatures, consumers calls for declarations of countries of origin and information on the conditions in which the good has been produced. These demands form the basis of what later becomes the Max Havelaar label.

-

1981

Launch of the campaign against the trafficking of women and creation of the FIZ

1981

Sex tourism and the trafficking of women are on the rise. In 1981, the Berne Declaration sues a bar owner and takes him to trial. The media echo is resounding. In 1985, the Berne Declaration proposes that an organisation dedicated to raising awareness about the causes of sex tourism and the trafficking of women, as well as possible courses of action, be set up. The (FIZ Advocacy and Support for Migrant Women and Victims of Trafficking) opens an information and meeting centre in Zurich. It actively supports women in Switzerland who are victims of trafficking at the political and social level.

-

1982

Launch of the Baobab Books children’s book collection

1982

Making children and young people aware of the inequalities that developing countries are subject to has always been part of the Berne Declaration’s mission. In collaboration with Terre des Hommes Suisse, the Berne Declaration sets up a fund entitled “the Third World Children’s Book Fund”, to support literature for children and adults written by authors from countries of the South. A “Baobab” series of works is published in 1988. Since 2011, Baobab Books has been an independent organisation.

-

1983

A momentous campaign against Galecron

1983

The Berne Declaration exposes confidential studies proving that the Swiss company Ciba-Geigy (now known as Novartis) is aware that Galecron is carcinogenic. The drug is banned in Switzerland because of the risk it poses to public health, and yet still sold in numerous developing countries. A large campaign is launched to put an end to these scandalous practices. In 1987, the company succumbed to pressure and announced the recall of Galecron.

-

1985

Game Mondopoly

1985

Using games to raise awareness is one of the approaches tried out by the Berne Declaration. Based on the famous Monopoly, ‘Tiers Mondopoly’ enables players to experience the daily lives of farmers from the highlands of Peru, and thus to understand the difficulties they face. Tiers Mondopoly has been translated into seven languages and has become a best-seller. In 1993, a large competition was organised to mark the Berne Declaration’s 25th anniversary!

-

1986

Campaigning for the return of the Marcos funds

1986

A scandal erupts when Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos is ousted, and it is revealed that Swiss financial intermediaries have accepted and managed plundered wealth. Several hundred million Swiss francs are found in Swiss bank accounts. The Berne Declaration campaigns for these funds to be seized. The Swiss authorities freeze the funds and a prolonged court case finally leads them to be returned to the victims of Marcos 20 years later. The scandal, followed by that of the Duvalier funds, gives rise to the development of Switzerland’s policy on illegal assets.

-

1989

Medi-Minus: the blockbuster information campaign

1989

“Nearly half of Swiss medicines sold in the South are useless, inefficient or even dangerous.” Published in 1989, these results make your blood run cold. To denounce the irresponsible practices of Swiss pharma companies, the Berne Declaration prescribes Media-Minus, a small information leaflet disguised as medicine packaging. Medi-Minus has been translated into six languages and over 100,000 of them have been disseminated, including by a large health insurance firm.

-

1992

Consumption causes Hunger campaign

1992

In the 1990s, it was widely believed that population growth was the cause of hunger and environmental pollution. Efforts to resolve the problems focused on birth control and family planning programmes in the Global South. However, there was rarely discussion about the fact that industrial countries, home to a quarter of the world’s population, use up three quarters of its resources. Through the Consumption causes Hunger campaign, the Berne Declaration shows that inequalities and the unequal distribution of resources – rather than birth rates – are the real causes of hunger in the world.

-

1997

“Let’s go fair” campaign

1997

The Berne Declaration and Terre des Hommes Suisse launch a large campaign for “trainers pro-duced in dignified conditions”. Whilst giants like Nike, Adidas or Reebok sell dreams with a barrage of publicity, we reveal what is going on behind the scenes by inviting consumers to write to big brands, calling on them to provide decent working conditions. Nearly 40,000 letters of protest are sent.

-

2000

Public Eye on Davos

2000

Whilst the entire world is looking at the World Economic Forum in Davos (WEF), which is hosting Presi-dent Bill Clinton, the Berne Declaration inaugurates a critical counter-summit to denounce the lack of transparency and democratic legitimacy of the WEF. Largely excluded from the official events, journalists enthusiastically cover Public Eye’s first sessions. Conferences lasting several days bring together renowned figures, human rights activists.

-

2001

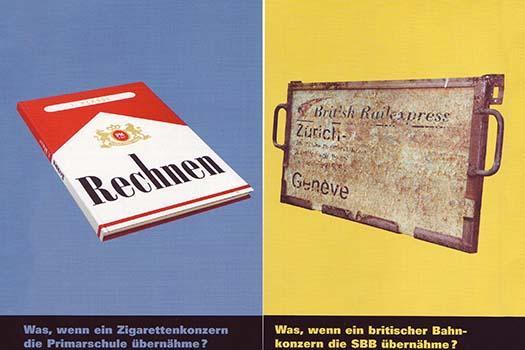

No to selling off the world’s public services

2001

The WTO is discretely negotiating a General Agreement on Trade in Services, promising to progressively liberalise the public education, health and service sectors. The agreement would only serve commercial interests, to the detriment of the public. The Berne Declaration asks people to imagine what it would be like if a food giant was responsible for the water supply! Thousands of protest letters calling for public services not to be liberalised are sent to the Federal Councillor, Pascal Couchepin. To date, the GATS negotiations have not been concluded.

-

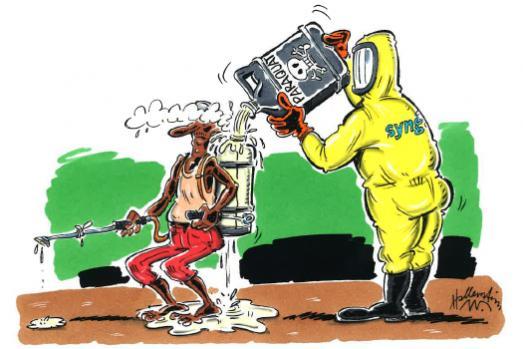

2002

Launch of the Stop Paraquat campaign

2002

In coalition with the international Pesticide Action Network, the Berne Declaration starts a long fight against paraquat. The weed killer, sold by Syngenta, is so toxic that it is banned in Switzerland and the European Union. Every year, it poisons millions in developing countries; studies link it to Parkinson’s disease and mutagenic potential. Sixteen years later, paraquat was banned in over 50 countries and numerous labels, producers and distributors renounced it, yet Syngenta continued to turn a deaf ear. We are still fighting against paraquat and other highly toxic pesticides sold by the Basel-based company.

-

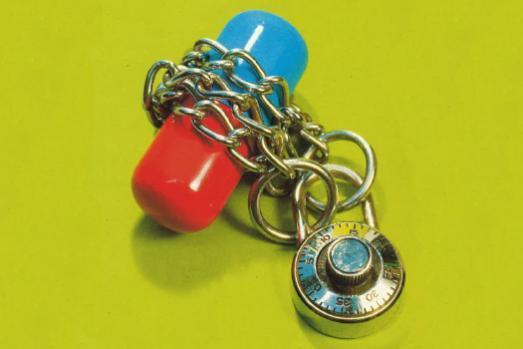

2003

Launch of the “obtain treatment – a right for everyone, including in poor countries” campaign

2003

Whilst Switzerland continues to provide its pharmaceutical companies with maximum protection of patents on the drugs, the Berne Declaration and the Swiss AIDS Federation – supported by some 40 other organisations – lobbied the Federal Council to demand that Switzerland work to implement the right to healthcare for all in developing countries, most notably generalised access to HIV/AIDS medication. They call on the pharmaceutical industry (and Roche in particular) to review its pricing policy for HIV/AIDS treatments protected by patents.

-

2003

Tax Justice Network Foundation

2003

During the European Social Forum in Florence, a group of activists discuss tax havens over coffee and decide to set up the Tax Justice Network. Their aim? To attack the ‘offshore’ system, not only because they see taxation as an essential means of mitigating the harmful effects of the unbridled capitalism of these years of neoliberalism, but because tax evasion is a key issue for developing countries. The Tax Justice Network – which the Berne Declaration is a founding member of and which is now known as the Global Alliance for Tax Justice – helped put the fight against tax evasion on the international community and of numerous countries’ agendas.

-

2005

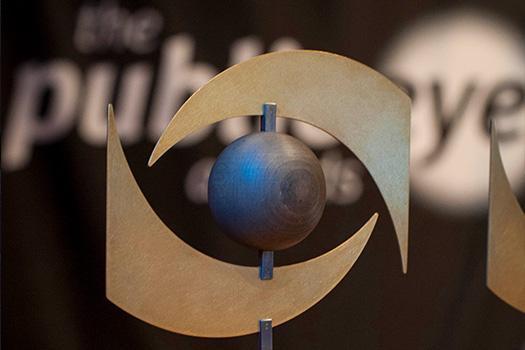

The shame prizes

2005

Whilst the World Economic Forumias trying to co-opt its critics by opening its doors, the Berne Declaration sets up the Public Eye Awards to attract media attention to cases of human rights violations and environmental damage caused by multinational companies. This strategy of naming and shaming gives victims a voice and facilitates support for civil society campaigns throughout the world. The last shame prizes were awarded in 2015, as the Berne Declaration has since focused on making its demands heard by the Swiss political community.

-

2008

A revolutionary T-Shirt

2008

To show that it is possible to produce clothes in fair conditions, the Berne Declaration produces a prototype T-Shirt. From the cotton fields of Burkina Faso to sewing workshops in India, a documentary follows the stages involved in making this piece of clothing through the image of Sasi Rekha, one of the many people who help to produce it. Our evaluation of the companies underlines the huge progress needed in terms of transparency and respect for workers’ rights.

-

2009

The seamstresses’ fight against Triumph

2009

The Swiss lingerie brand Triumph fires over 3,600 workers in its factories in Thailand and the Philippines without consulting trade unions. With the support of the Clean Clothes campaign, the workers file a complaint against Triumph with the OECD’s Swiss National Contact for the violation of the OECD’s guiding principles – to no avail. In 2010, the seamstresses decide to produce their own line of underwear, “Try Arm”. The Berne Declaration facilitates the sale of their underwear in Switzerland – the garments symbolise their struggle for better working conditions in the textile industry.

-

2009

Swiss chocolate: the child labour scandal

2009

The Berne Declaration launches a shock campaign to denounce Swiss producers’ inaction towards child labour on cacao plantations in West Africa. Despite the fact that the industry has long acknowledged the problem, most companies have not taken any credible measures to address it. Two of the main Swiss companies active in this sector, Nestlé and Barry Callebaut, do not even deign to answer our questions. This campaign marks the start of our awareness-raising work about the dark side of the sweet treat that the Swiss are so fond of.

-

2009

An unprecedented victory in the Ilisu dossier

2009

The Federal Council and Swiss Export Risk Insurance announce their intention to definitely retreat from the Ilisu dam project in Turkey. For the Berne Declaration, this marks the result of five years of struggle to ensure that the dam’s construction would only be started if the World Bank’s social and environmental standards, particularly with regard to cultural assets and the displacement of people, are respected.

-

2009

Our fight against patents on life

2009

The international coalition No Patents on Seeds, co-founded by the Berne Declaration, submits 100,000 signatures opposing patents on plants and animals to the European Patent Office. Tomatoes, broccoli, peppers – a fight against the manoeuvring of giants such as Syngenta to take control of seeds in a quest for profit, and to guarantee food security for all people. In 2016, the coalition achieved the revocation of an abusive Monsanto patent on melons.

-

2010

A Living Wage for All campaign

2010

How much more do seamstresses need to earn to be able to live in dignity? 10 cents per T-Shit, a ridiculous sum compared to the huge profits of large fashion companies! Whilst hundreds of thousands of workers take to the streets in Bangladesh and Cambodia to demand better working conditions, the Berne Declaration runs an awareness-raising campaign. Over 31,000 protest notes were sent to companies calling them to guarantee a living wage throughout their supply chains.

-

2011

Launch of the Rights Without Borders campaign

2011

How can you combat the impunity enjoyed by multinationals? The Berne Declaration helps to launch the Rights Without Borders campaign. Through a petition signed by 135,285 people, a network of NGOs calls on the authorities to introduce binding rules requiring companies registered in Switzerland to respect human rights and environmental standards all around the world. After a promising start, the debates in parliament are cut short in 2015 due to pressure from business lobbies. The coalition decides to launch an initiative on the topic – so David is fighting Goliath with the support of the public!

-

2011

The Berne Declaration publishes the “Swiss Trading SA”

2011

Swiss Trading SA is the result of a long investigation and the first major book on the Swiss natural resources sector. It shines a spotlight on Switzerland’s central role as main commodity trading market as well as the responsibility of giants such as Glencore, Trafigura & Cie in the resource curse that afflicts producing countries. The Berne Declaration thus puts the problems linked to this opaque sector on the media and political agenda. Amid the uproar, 15 statements are made about the subject in parliament. The publication marks the beginning of a long campaign to fight against the impact of a highly risky business model.

-

2012

The (nearly) naked truth about Swiss uniforms

2012

Investigations carried out by the Berne Declaration reveal that Swiss police uniforms and even its army’s camouflage uniforms are made in very controversial conditions – seamstresses in Macedonia are only earning CHF 122 per month! Using a very humorous video, the Berne Declaration calls on Switzerland to clearly embed social standards in the federal law on government procurement, which is under revision. It marks the beginning of a long advocacy campaign!

-

2012

The Berne Declaration bolsters its national body

2012

From this point on, the Berne Declaration only has one national committee, with equal representation for linguistic regions. Pierrette Rohrbach is appointed president of the new body. The organisation’s leadership becomes comprised of four ‘heads’.

-

2013

The “Berseticum Forte” against abusive clinical trials

2013

The Berne Declaration takes an interest in the outsourcing of clinical trials to developing and emerging countries, where violations of ethical standards are commonplace. In some cases, patients are unaware that they are taking an experimental treatment and often they no longer have access once the trial has finished. The checks carried out by Swissmedic do not guarantee that medicines sold on the Swiss market have been tested in ethical conditions. In a campaign, the Berne Declaration calls on Alain Berset, the minister of health, to implement concrete measures to address the scandal.

-

2014

ROHMA, a visionary proposal

2014

By setting up a fictitious oversight body inspired by FINMA (the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority), the Berne Declaration puts forward the first ideas about how the Swiss natural resources sector could be regulated. The website www.rohma.ch describes the entire authority and the legislation that would govern its activity. This measure makes it possible to fight the resource curse by imposing due diligence and transparency requirements on companies active in Switzerland. Mark Pieth, or even Bernard Bertossa, are part of the symbolic board of this organisation, which is inspired by – but an improved version of – FINMA, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority.

-

2015

An initiative for responsible multinationals

2015

Together with over 80 organisations, the Berne Declaration launches an initiative for responsible multinationals. The text it produces seeks to instil a duty of diligence in terms of human rights and environmental standards by obliging companies to assess the risks linked to their activities, take measures to address them and to make these public. In the event of negligence, companies could be held accountable for damage caused by their branches abroad. Dick Marty, Cornelio Sommaruga, Micheline Calmy-Rey amongst others sit on the committee. Having gained 120,000 signatures, the initiative was submitted in Berne in October 2016. The vote will take place in 2019.

-

2015

A scathing report on Valcambi’s gold

2015

How is it possible for Switzerland to import tons of gold from Togo when the country doesn’t produce any? The Berne Declaration reveals that the gold in question comes from artisanal mines in Burkina Faso, where it is extracted by children in horrendous conditions. The fruit of their work is then transported to Togo by smugglers, before being imported to Switzerland by a Geneva-based company that resells it to the refinery in Tessin. Commented on my numerous media sources, these revelations highlight the need to regulate the Swiss natural resources sector.

-

2016

The Berne Declaration becomes Public Eye

2016

On 21 May 2016, the Berne Declaration’s members assemble to approve the new name: “Public Eye”, reflecting the organisation’s core mission. Through investigations, advocacy and campaigns, Public Eye fights injustices originating in Switzerland by demanding greater equality and respect for human rights around the world. The organisation also updates its visual image and the design of its magazine.

-

2016

Stevia : a sweetener with a bitter taste

2016

Public Eye unveils the hidden face of the very lucrative stevia market. To improve the image of their fizzy drinks, seen as too sugary and synthetic, Coca Cola and PepsiCo are marketing products sweetened with steviol glycosides to a great publicity fanfare. The problem is that the Guarani people of Paraguay, who discovered the properties of this plant, are not benefitting from any of the commercial profits, in violation of the Convention on Biological Diversity. 260,000 people sign Public Eye’s petition against this case of bio-piracy. In 2016, Public Eye convinced numerous companies to start discussions with the Guaranis on a profit-sharing agreement.

-

2016

Public Eye campaigns against “Dirty Diesel”

2016

Public Eye reveals how Swiss traders are taking advantage of weak standards in Africa to produce and sell highly sulphuric fuels, banned in Europe, thus contributing to the explosion of pollution levels in African cities. The media response to our report and our symbolic action (a container containing polluted air from Ghana is brought to Switzerland) is overwhelming. A petition signed by nearly 20,000 people calls on Trafigura to end this illegal trade. Whilst Swiss companies turn a deaf ear, five West African countries decide to significantly reduce the sulphur content allowed in diesel. A victory that helps to protect the health of over 250 million people!

-

2017

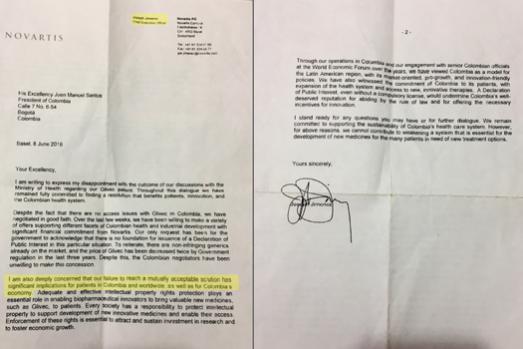

Compulsory licence in Colombia

2017

Public Eye reveals confidential documents written by Novartis to the Colombian Ministry of Trade and Industry. They reveal how the Swiss pharmaceutical giant is pressuring Colombia by threatening to resort to a private international dispute resolution court to avoid having to obtain a compulsory licence for its landmark anti-cancer treatment, Glivec. At the beginning of 2018, a new letter personally signed by the CEO of Novartis and addressed to the President of Colombia sheds additional light on the aggressive lobbying methods used to pressure the Colombian authorities.

-

2017

Public Eye reveals Gunvor’s secrets in the DRC

2017

After two years of investigation, Public Eye reveals the dubious practices of the oil trader Gunvor in the DRC. Had the trader paid bribes to the president’s cronies to obtain juicy contracts at the cost of the Congolese people? Gunvor oppresses one of its former employees, but a secret video, revealed by Public Eye, greatly embarrasses the company. The day before the publication of Public Eye’s report, Gunvor announces to the news agency Reuters that a court case had been opened against it. New information casts aspersions on the Geneva-based trader’s defence.

-

2017

A criminal charge against Glencore

2017

Following the revelations of the Paradise Papers, Public Eye files a criminal complaint with the Federal Prosecutor’s Office regarding the activities undertaken by the Swiss natural resources giant, Glencore, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The topic: its highly risky partnership with businessman Dan Gertler and the signs of misappropriation surrounding the acquisition of copper mines in very advantageous conditions. At the end of January 2018, the media reveals that Gertler is being investigated by the US authorities for corruption in the DRC. The money allegedly passed through Swiss bank accounts – the US requests legal cooperation from Switzerland.

-

2018

The Public Eye Investigation Award

2018

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, Public Eye launches an investigation prize to support journalists investigating stories in countries where human rights and environmental standards are violated in the quest for profit. Their insight is essential when it comes to denouncing injustices originating in Switzerland. The jury includes renowned journalists: Will Fitzgibbon (ICIJ), Anya Schiffrin (Columbia University) and Oliver Zihlmann (Tamedia). In April, there will be a crowd-funding initiative for the chosen projects.